VILLA MALPENSATA, SPAZIO MOSTRE

KAKEMONO is the most extensive exhibition ever devoted to Japanese painting. The exhibition, curated by Matthi Forrer, retraces five centuries of the Japanese figurative tradition between the 16th and 20th centuries, through 90 kakemono, arranged along a thematic path that allows us to explore in depth the substance of pictorial languages, from the unpublished collection, collected with philological care by the Turin-born Claudio Perino. The exhibition, produced by the Lugano Culture and Museums Foundation and the Turin Museums Foundation, is supported by the City of Lugano, the Republic and Canton of Ticino – SWISSLOS Fund, and the Ada Ceschin and Rosanna Pilone Foundation. “Kakemono – states Francesco Paolo Campione, director of MUSEC – is a project that was born with a precise idea: to recount five centuries of Japanese art history, taking the public by the hand on an emotional journey of forms and subjects; a journey capable of restoring the peculiarity not only of painting but, more widely, of visual representation in Japanese civilisation”.

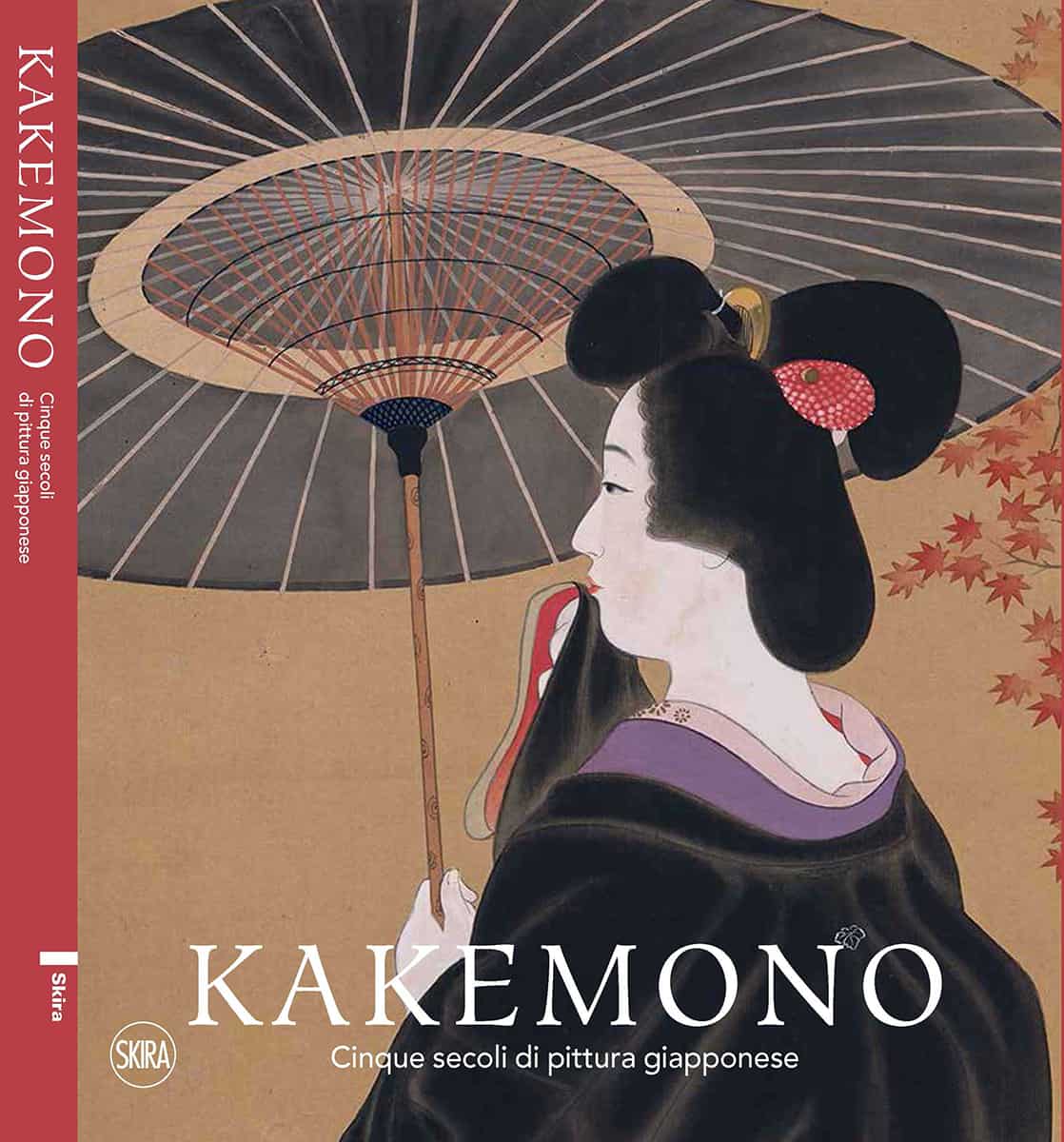

What is kakemono?

The kakemono, a widespread genre in East Asia, consists of a precious cloth or paper scroll, painted or calligraphed, which is hung on walls during special occasions or used as a decoration according to the seasons of the year. Unlike Western canvases or tables, kakemono have a soft structure, and are conceived for a chronologically limited use: they are in fact works that participate in time and movement, as they are displayed in the alcove of Japanese homes or left to swing for a few hours outside, perhaps in the garden, for the tea ceremony. Works that, in the variety of their subjects, describe the ineffable beauty and the passing of time, reflecting a typically oriental aesthetic and philosophical conception. “When Japan,” writes Matthi Forrer in his catalogue essay, “began to regard the Chinese as ‘big brothers’ in many fields such as the arts, crafts and technology, it was automatic to recognise the importance of Chinese literary and theoretical sources on painting. […] As Chinese painting was mainly ink on paper or silk – with precise rules that warned against using colours unless it was really necessary – Japanese painting mainly uses black ink on paper. This style of painting would be formalised from the 14th century in the – often rather academic – tradition of the Kanō school. Among the most frequently used subjects were fierce animals such as dragons and tigers, or plants, flowers and birds, all loaded with symbolic meanings that helped to establish and consolidate the social status of the owners of the works. The exponents of this Kanō school founded a widespread network of painting academies throughout Japan, which from the 15th century to the end of the 19th century enjoyed the support of the ruling classes. Indeed, the samurai, Buddhist clergy and the wealthy relied on them to produce kakemono, following the fashion of the period. Only from the 17th century onwards did an emerging urban class of artisans and merchants encourage the development of more diversified pictorial interpretations that focused on more naturalistic subjects and real-life scenes. Other painters then broke out of the rigidity of these traditional schemes, favouring innovation and developing more personal styles.

The Exhibition Itinerary

The exhibition itinerary is divided into five thematic sections (Flowers and Birds; Anthropomorphic Figures; Animals; Various Plants and Flowers; Landscapes) and features the works of the major artists of the time, such as Yamamoto Baiitsu (1783-1856), Tani Bunchō (1763-1840), Kishi Ganku (1749-1838), Ogata Kōrin (1658-1716). The exhibition opens with paintings of flowers and birds (kachō-ga) that play on an allegorical association taken from haiku poems, and continues with those depicting anthropomorphic figures, at first limited to some Buddhist deities, followers or disciples of Buddha, portraits of Shinto figures, or characters borrowed from Chinese tradition. It was only in the 18th and 19th century that ordinary people also began to appear. From the analysis of the iconography of animals, which, unlike that of birds, are represented sparsely, we come to the section of paintings featuring plants and flowers, linked to the months and seasons. Among the plants, bamboo has an important symbolic meaning, conveying a sense of flexibility, resistance and security. For many scholars and men of letters, the pictorial representation of bamboo was a very important exercise, closely related in its technical characteristics to calligraphy, so much so that some artists devoted their entire lives to it. The exhibition closes with landscape paintings that convey an idealised concept of nature. In such works, one often finds rivers, lakes, streams, puddles or brooks in the foreground and mountain peaks in the background and, on a smaller scale, bridges, temples, pavilions, buildings and small human figures. It is particularly interesting to note that this genre is almost always done in ink alone, with rare notes of colour. The exhibition is enriched by two original Samurai suits of armour and several albums of Japanese photographs from the late 19th century, with richly decorated lacquer covers, from the MUSEC collections.