VILLA MALPENSATA – SPAZIO CIELO

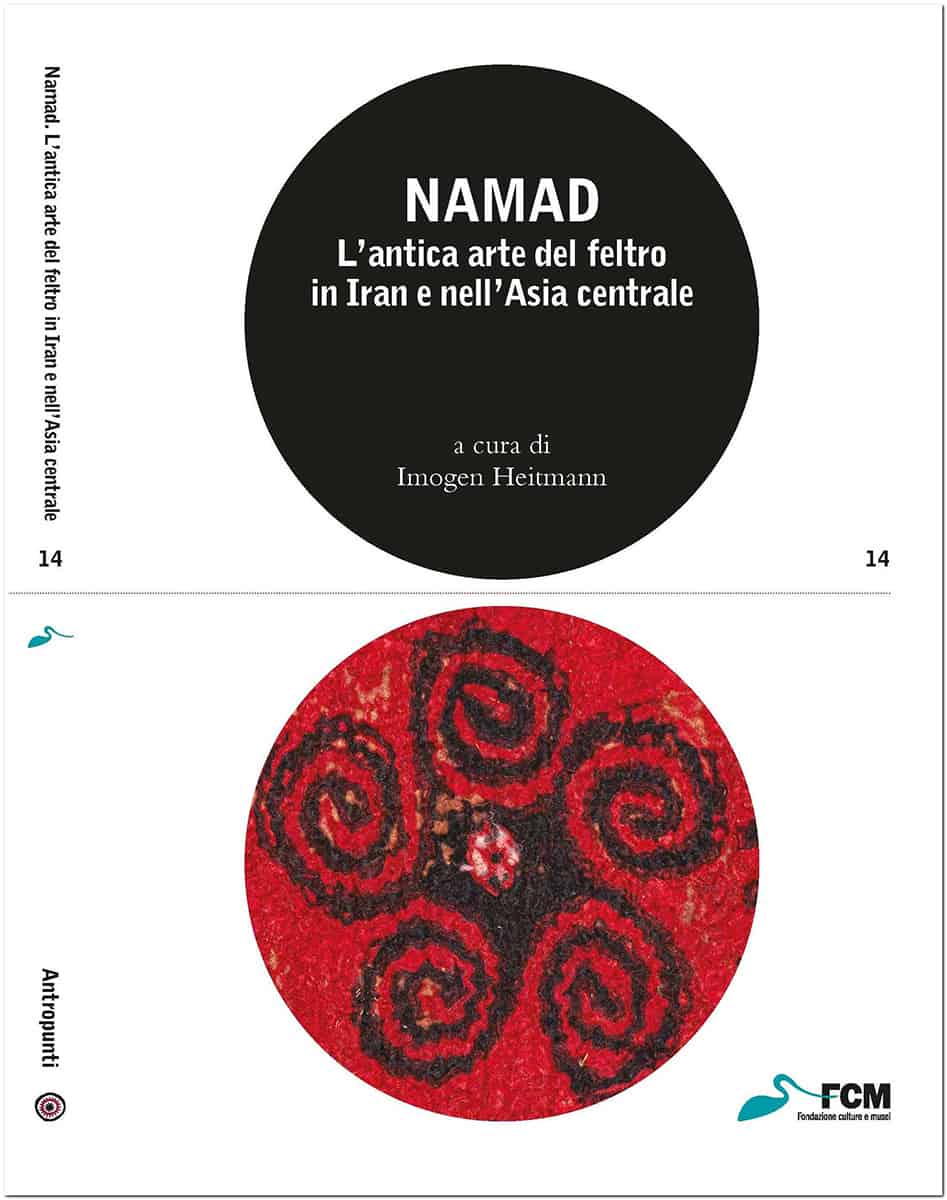

Felt (namad, in Farsi) has accompanied the lives of nomads for thousands of years in a vast geographical area, including Turkmenistan, Iran, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Afghanistan. Traces of them can be found in the chronicles of Marco Polo, but in the West they have long remained in the shadows. It was in the wake of the avant-garde’s attraction for the so-called ‘primitive’ arts that the archaic and mysterious character of the ornamental motifs of felts awakened the interest of artists and collectors. MUSEC’s careful research brings to light the complexity that characterises both the splendid artefacts and the cultures that produced them. Set up in the Spazio Cielo on the second floor of Villa Malpensata and curated by Imogen Heitmann, the “Namad” exhibition offers visitors the unique opportunity to discover sixteen large-scale works, including felts, embroidered textiles and traditional tent elements (iurta): all evidence of how felt was of fundamental importance to the lives of the peoples of Iran and Central Asia. The exhibited works were selected from those collected by Sergio Poggianella, gallery owner and art expert, as well as President of the Foundation of the same name in Rovereto; forty of his felts now belong to the MUSEC permanent collections.

A ‘simple’ but complex technique

A legend passed down among felt makers in Iran tells that the shepherd son of Hazrat Suleiman (King Solomon) tried, unsuccessfully, to use flakes of sheep’s wool to produce a non-woven cloth. He beat the wool, weeping hot tears over it, and the action of beating the dampened wool transformed the flakes into cloth. Today, this shepherd is still the patron saint of felt makers in northern Iran. One of the most distinctive aspects of felt is its manufacturing technique. Unlike woven and knotted fabrics or carpets, it is achieved by selecting, cleaning and ‘assembling’ the wool fibres through the process of fulling. The technique relies on the physical, chemical and mechanical properties of natural wool, as well as a series of specific movements, steps and techniques that enable the production of works of different genres and styles. Precisely because it is so immediate and easy to manufacture, some scholars believe it to be one of the earliest forms of cloth ever created by man.

Felt patterns: traces from medieval Persia

Felts show the existence of a variety of techniques and an iconographic variety. Their decorative motifs make up a codified universe of stylised signs that are difficult to interpret, shared by several groups within large geographical areas and also spread over numerous other media. In this sense, the Persian miniatures of the medieval period are particularly relevant. They were created following a major historical moment: during the 13th century, the Mongols – initially under the leadership of Genghis Khan – occupied Central Asia, integrating the various Turkic peoples of the region. At its height, the empire, which was the largest on the globe, covered much of Asia and Eastern Europe. The great Turkish-Mongolian rulers had literary and illustrated works of contemporary history produced in which the traditional felt tents and their furnishings appear. The drawings allow us on the one hand to understand what the felt curtains of the past looked like, and on the other hand to observe the imaginative work of the miniaturists. Although it is highly unlikely that the felts were entirely covered in gold embroidery, they were undoubtedly a fundamental element of Central Asian material culture.