VILLA MALPENSATA

An extraordinary mosaic of six hundred miniature masterpieces expressing the aesthetic finesse and technical mastery typical of Japan. Presented to the public for the first time, the postcards on display are selected from the almost six thousand images in the Ceschin Pilone Collection, the largest in Europe. Set up in the Spazio Maraini of Villa Malpensata, the exhibition presents six hundred postcards, carefully selected by the curator Moira Luraschi to restore to the visitor the extraordinary creativity and executive refinement with which Japan has elevated the postcard to a true genre of art. The Collection, originally assembled by Marco Fagioli, was placed on deposit at MUSEC in 2018 by the Ada Ceschin and Rosanna Pilone Foundation, MUSEC’s long-standing partner in the field of photography and the art of the Orient. The extraordinary collection excellently represents the multiplicity of subject techniques used in Japan in the golden years of the postcard, from the early 20th century to the First World War, and in the decades that followed.

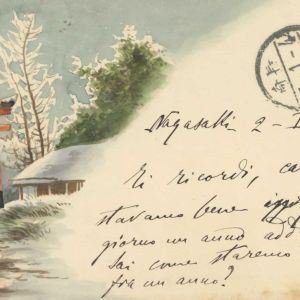

Today’s picture postcard is derived from the famous, unillustrated Correspondenz-Karte, first issued by the Austro-Hungarian Post Office on 1 October 1869. As it was a pre-franked card, whose message was exposed for all to see, it enjoyed a reduced tariff, which most probably made it a success in all countries. Initially, the use of postcards was only domestic and their production the prerogative of individual national postal administrations. Japan adopted the postcard in 1873. With the creation of the Universal Postal Union in 1874, which Japan joined three years later, the country switched to an efficient mail service connected to the rest of the world, leaving behind the tattooed, loincloth-clad postmen (hikyaku) who ran half-naked through the streets and aroused the curiosity of the first Westerners visiting the country. In 1900, Japan, as well as other nations, liberalised the production of picture postcards in which the message and postage was written on the back, i.e. on the side of the picture, while the address was written on the front. The liberalisation of the production of postcards inevitably led to exponential growth and an increasingly accurate and refined search for images to illustrate them.

In 1907, the British Post Office adopted the so-called divided back postcard in which the front was divided by a vertical line at 2/3 of the space: the larger space was reserved for postage and address and the smaller for the message. This innovation constituted a real revolution in the production of postcards, because in this way an entire side was available for illustration. This innovation was soon adopted in many other countries. The simultaneous evolution of printing techniques did the rest and led to the production of small masterpieces in postcard format.

Japan in postcards

Some subjects of Japanese postcards, although taken up in postcards also produced in other parts of the world, retain their own characteristics.

The series of postcards constructed as polyptychs, to be read visually in the Japanese manner from right to left, depict major events in local history, represented as in a painted horizontal scroll (emakimono).

Disasters and accidents, in particular the earthquakes for which Japan is sadly famous, become events to be immortalised and remembered on postcards, according to a cyclical vision of history as the oriental one is, in which the present becomes the past and can return in the future. The postcards, although mostly aimed at portraying the effects of natural disasters, often play on the dual representation of ‘before’ and ‘after’. There is also no lack of emphasising of the drama, such as the reddish flames among the rubble of earthquakes, a free interpretation of the scene made by the printer.

Contemporary political and military events are also seen as part of the history that was being constructed. The events of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 were by far the most represented on postcards of the time, and not only on Japanese postcards. These events were often depicted in even satirical ways, with Japan personified by a small soldier fighting (and winning) against the mighty Russian power. Similarly, Japan’s increasingly aggressive policy of conquest in East Asia also became part of history and was celebrated on postcards.

And again, the passage of time, as well as the local tradition of New Year greeting cards, are referred to in the nenga-ehagaki, the calendar postcards, which also take up the technique of polychrome woodcuts.

A Japanese genre is that of the erotic postcards, which became popular in the West at the beginning of the century; these images replaced the xylographic prints of an explicitly erotic character (shunga) widespread in Japan since the 16th century. Since shunga were fiercely censored in those years, erotic postcards, in which semi-nudity was ‘justified’ by the desire to show local customs, became the only permitted substitutes.

Techniques

Graphic Arts and Photography

The many materials and techniques used in Japan to make postcards created a real mixture of local elements and western styles.

Lacquer (urushi) was one of the most frequently used traditional materials to ennoble postcards, embellishing details or creating whole, more or less stereotypical images, made with a western taste. Lacquer is a transparent sap produced by a shrub. After long processing, it becomes a shiny dark-coloured liquid that can be applied with a brush. Being a sticky material, lacquer could be mixed with pigments or gold dust, as in some of the postcards in the Collection.

Next to those worked with a traditional material like lacquer, there are also postcards made with oil colours, a typical prestigious material, but this time from the Western painting tradition. In the oil postcards, the oriental landscapes totally bend, even in style, to Western taste, like small pictures in a bourgeois drawing room of the early 20th century.

As for the techniques used to make postcards, the most widespread local craft was the chirimen, in which hand-creped paper is printed with polychrome woodcut. By contrast, modern means of photographic reproduction were introduced from the West, which made it possible to produce postcards with photographic images engraved on wood.

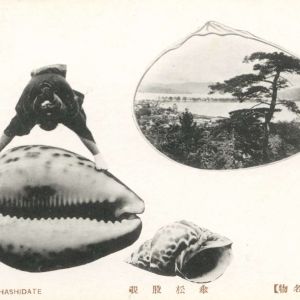

Greater interaction between different styles, as well as great experimental freedom are particularly visible in those postcards that play in the space between graphics and photography, which are often impossible to classify as graphic or photographic tout court, which can be done with contemporary postcards produced in the West. Photomontages, decoupage, collage, the coexistence of graphic elements with photographs, handmade work, dry printing, gaufrage, and the use of different finishing materials such as lacquer or mica make Japanese postcards small works of art, the result of highly refined workmanship that has no equal in the world.

Contemporary with this artistic elaboration is also linguistic and political experimentation such as the use of Esperanto, documented by some postcards of the time. The postcards truly become an expression of a changing world, in which aesthetic and communicative languages are increasingly interconnected.