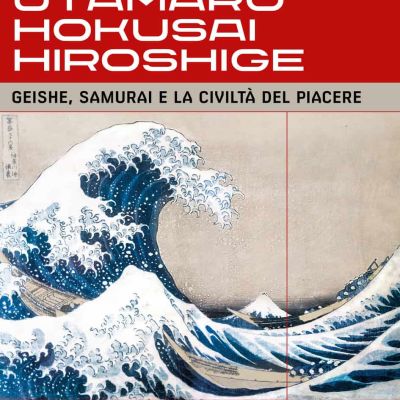

GEISHAS, SAMURAI AND THE CIVILISATION OF PLEASURE

TORINO Società Promotrice delle Belle Arti

The exhibition, curated by Francesco Paolo Campione, director of MUSEC – Museo delle Culture di Lugano, produced by Skira, in collaboration with MUSEC and the Società Promotrice delle Belle Arti di Torino, with the patronage of the Municipality of Turin, analyses the Japanese universe through a thematic itinerary, divided into nine sections, with over 300 masterpieces, some of which have never been presented in Italy: prints by the greatest masters of ukiyo-e, such as Hokusai, Hiroshige, Utamaro, Kuniyoshi, Yoshitoshi, Sharaku, as well as samurai armour, kimonos, theatre masks, rare print matrices, precious female ornaments, stone sculptures, and banners, from the collections of the MUSEC in Lugano, the Museum of Oriental Art in Venice, the Museum of Oriental Art in Turin, the Civic Museum of Oriental Art in Trieste, the Fondation Baur Musée des Arts d’Extrême-Orient in Geneva and important private collections.

The exhibition is proposed as an original reconstruction, in all its aspects, of the ‘civilisation of pleasure’, a peculiar historical-artistic season of Japan – the Edo period (1603-1868) – in which the country, pacified within its own borders and locked in a policy of isolation from the rest of the world (sakoku) led the wealthy merchant class (chōnin), unable to buy landed property, to devote themselves to the pleasures of existence, such as kabuki shows, frequenting geishas in teahouses and buying extraordinary works of art.

The exhibition is accompanied by a 368-page catalogue edited by Francesco Paolo Campione, Marco Fagioli and Moira Luraschi. SKIRA Editions, 2023

The exhibition opens with the “images of the floating world” (ukiyo-e), woodcut prints made on wooden matrixes that became synonymous with “modern”, fashionable, and ended up expressing a sort of philosophy centred on the taste for a pleasant existence and, as far as possible, fulfilling personal desires, interpreted by artists such as Hiroshige, Utamaro, Kuniyoshi and Hokusai; Of the latter, the exhibition presents the fifteen volumes of Manga, a veritable encyclopaedia of drawing, in which the Japanese artist portrays everything he saw or that his mind conceived, from landscapes to natural and supernatural elements, from everyday life to human beings and deities, from flora to fauna.

The exhibition continues with reconnaissance on subjects typical of Japanese art, such as nature seen both in its more landscape-like aspect, interpreted for example in Hiroshige’s prints, and in what was recognised as a true pictorial genre of ‘flowers and birds’ (kachōga), which, in their symbolic juxtapositions, also act as signalling elements of the seasons. Sparrows with winter camellias blooming amidst the snow symbolise the incipient spring, which in the traditional calendar fell between January and February; cherry blossoms (sakura) are typical of late spring; peonies (botan) and irises signal summer; and bellflowers (kikyō), finally, are characteristic of autumn.

Ephemeral pleasures were also among the most documented subjects in Japanese prints; such as that of the kabuki theatre, the popular spectacle par excellence. Prints depicting the actors in these plays will be on display in Turin. These are works with elegant and refined traits that, over time, had a peculiar evolution: from the “primitive” works of the 17th and 18th centuries aimed above all at outlining the physiognomy of the actors and their stage accessories, to the colourful, rich and hyper-expressive multi-sheet compositions of the late Edo period, in which the artists tried to reproduce all the scenic richness.

This section also includes an official programme from 1890 illustrated and printed in black with a woodcut matrix, a banner (nobori hata) from the mid-19th century made of hand-painted fabric, used as an advertising sign for kabuki theatre performances, as well as more than 30 popular masks from nō and kyōgen theatre.

Particularly interesting is the figure of the artist Sharaku, about whose identity speculation abounds; some think he was an actor, some lean towards a pseudonym used by a group of highly innovative artists and some claim that Hokusai was behind his name. Beyond all conjecture, the faces of the actors of the kabuki theatre portrayed in Sharaku’s works allowed us to interpret the psychology of the characters portrayed on stage and revealed a temporary emotion raised to a spiritual level and, sometimes, the very essence of a personality.

The female universe was also profoundly investigated. On the one hand, aspects of the daily life of women of various ages and social backgrounds were explored, as in the prints of Tsukioka Yoshitoshi or in the triptychs of Miyagawa Shuntei depicting women engaged in typical activities alongside plant elements to recall the various months of the year, while on the other hand, erotic woodcuts (shunga) established themselves as a genre of primary importance. In their works one finds direct testimony and personal emotional participation in the representation of the pleasures of sexuality, enriched by knowledge and quotation, sometimes even philological, of a literary production full of sensuality.

The exhibition continues with the section documenting prints depicting warriors and heroes from the Japanese tradition (musha-e). These owe their typical appearance to the work of Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798-1861), who devoted much of his attention to them from 1827 onwards. His characters are dressed in splendid clothes and portrayed while fighting or performing heroic deeds, facing enemies and monstrous beings depicted with extraordinary meticulousness, in a lively landscape rich in descriptive details.

Also on show will be Hokusai’s so-called warrior books, true masterpieces of drawing in which the artist moves between nature and the supernatural, placing the action of the hero at the centre of his figurative research.

The exhibition closes with a room dedicated to the iconographic and stylistic legacy of ukiyo-e, with a spectacular immersive installation that introduces the viewer to Hokusai’s Great Wave, which, on the one hand, synthesises in an image the sense of transience and temporariness of human life in the face of the unstoppable force of nature and history, and on the other, expresses the desire not to heroically oppose the facts of life, but to let oneself go, guided by an existential philosophy based on pleasure.